Armenian News Network / Groong

On the

collapse of the 1918 First Republic and the 1921 Russo-Turkish Treaty of Kars

December 19, 2021

By Eddie

Arnavoudian

LONDON, UK

The Collapse of the First 1918-1920

Armenian Republic: lessons for today?

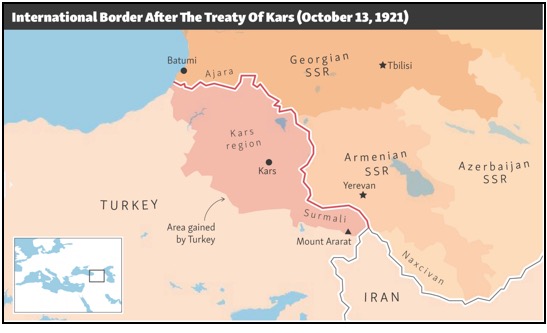

October 2021 marked a hundred years since the infamous 1921

Turkish-Soviet Treaty of Kars that ratified Armenia’s much, indeed unjustly,

reduced borders with Turkey that remain in place to this day. On the occasion

of this anniversary many a press pundit denounced the Treaty without

considering its wider context, something that would bring to the fore those

critical challenges the 1918 Armenian First Republic confronted but failed to

overcome.

Fig. 1: Screenshot from RFE/RL

article More Turkey: The Soviet Border

Before and After The Treaty of Kars.

Our habit of blaming others for our misfortunes is a

paralyzing defect blinding us to any examination of those spheres in which our

own actions and moves could make a difference. We have no means to alter the

strategy and policy of the big or regional powers. But we do have means to act

in ways that reinforce our strengths and give us at least a few cards to deal

with external powers.

I have framed some of the issues as a commentary on two

important books and that in rather extreme, polemical form in order to more

starkly bring to the fore those areas in which our traditional thought lacks

versatility, to put it mildly. My intention is not to offend but to spark

debate!

PART

ONE

The experience of the First Armenian Republic founded on 28

May 1918 is replete with alerts for today’s Third Armenian Republic undergoing

existential crisis. How did the First Republic come to its end on 2 December 1920

after a mere three-year existence? A common claim is that it fell victim to a

pitiless Soviet Russian-Turkish conspiracy.

It is alleged that two malign powers, Soviet Russia and Turkey, divided

Armenia between them. The carve up thus satisfied Kemal Ataturk’s ambition to

recover the Armenian controlled Kars and Ardahan regions that the Ottoman

Empire had lost to Tsarist Russia in the 1870 Russo-Turkish War. It also

fulfilled Bolshevik Russia’s ambition to re-establish Russian mastery over

eastern Armenia and the Caucuses. This joint project, it is insisted, had no

room for an independent Armenia.

The argument is advanced at length by two fiercely

anti-Soviet historians, Diaspora-based Roubina Piroumian [1] and Armenia-born

Lentrush Khurshutyan [2]. As the editor’s introduction to Khurshutyan’s volume

puts it, the First Republic was destroyed as a result of ‘Kemalist and

Bolshevik expansionist programs (LK3).’ It is a faulty calculus, however, that

ignores the role and responsibility of the Armenian state and government in the

fortunes of the First Republic. In this narrative the leaders of the Republic

appear powerless, dependent entirely on the actions of foreign states. Focusing

one-sidedly on the indubitably weighty Turkish and Russian role, no account is

offered of what the Armenian state and elite did or did not do domestically and

internationally to bolster Armenian positions and mitigate the damages of

unfriendly foreign ambitions. It is as though Armenian actions counted for

nothing before the almighty force of foreign ‘expansionist programmes.’

The assiduous removal of Armenian agency from the equation

of the First Republic’s demise has given birth to a tawdry historiographical

theology of Russian ‘betrayal’, as if the Bolshevik Russian state had a moral

obligation to sacrifice its own interests for another state, and in this

instance an Armenian state that was doggedly anti-Bolshevik, an Armenian

government that in solidarity with the West waging war on Russia, could not

even bring itself to begin official relations with the Bolshevik government

until May 1920 (RP207), just seven months prior to the Republic’s

disappearance.

Such approaches to the history of the First Republic do more

than just sidestep the failure of Armenian elites to strengthen national state

foundations or sway the regional balance of power to its advantage. They

additionally lack awareness of deeper objective socio-historical dynamics that

severely undermined Armenian nation formation in the early 20th

century and so rendered any form of statehood singularly insecure and

vulnerable to internal disintegration and external aggression.

I. Crisis of Armenian nation and

state formation

The end of the 1914-1918 First World War and the collapse of

the Ottoman and Tsarist empires accelerated the process of nation and state

formation in former imperial territories. As the victorious Allied powers – the

UK, France and to a lesser extent the USA – battled to seize and carve up

previously Ottoman and Tsarist controlled lands, the peoples of the Caucuses,

of Asia Minor and the Arab world fought to found their own independent nation

states.

In this historic tide, the Armenian people were in an almost

impossible position (Note 3). Within Ottoman and Tsarist occupied Armenian

communities, across a century and more, imperial states together with

collaborationist Armenian elites systematically narrowed and even eliminated

essential territorial, demographic, social, economic, and political

preconditions for Armenian national development. By the end of WWI across both

western Ottoman and eastern Tsarist ruled Armenian communities, nation

formation was left bereft of firm, enduring foundations.

In western Armenian homelands, the 1915 Ottoman-Young Turk

organized Genocide and mass deportations were terminal blows to any form of

Armenian national development let alone statehood in what was by far the

largest segment of historic Armenia. With 1.5 million Armenian inhabitants

slaughtered and hundreds of thousands more deported, their land, property and

wealth destroyed or confiscated, the demographic and economic pillars of

Armenian life were smashed irrevocably. There was little prospect thereafter

that any segment of western Armenia that had been homeland to Armenian

communities for tens of centuries could form part of any new Armenian

nation-state in the region.

Structures for Armenian nationhood in eastern Armenia,

located in the Caucuses, were also desperately shaky. Powerful Armenian

economic elites, indispensable to successful nation-formation were based

outside Armenia, in Georgia and Azerbaijan. Tbilisi and Baku-based Armenian

Diaspora elites turned their noses up at the envisaged territories of a Caucasian

Armenian state. For them Armenia, lacking in wealth and any significant natural

resources, was an undesirable backwater compared to the lucrative regions of

Georgia and Azerbaijan that they lived and operated in. Roubina Piroumian

writes that in the first decades of the 20th century:

‘Yerevan was an insignificant rural town ignored by the

Armenian rich and by the intelligentsia…(RP138).’

Significant demographic diversity in the region also

precluded the formation of a cohesive Armenian national, social

and political entity, for as Piroumian adds:

‘…in those territories allocated to Armenia half the

population was Turkish or Kurdish (RP138).’

Eastern, Caucasian Armenian ruling classes were naturally

opposed to the idea of independent Armenian statehood preferring instead a

regional federation of Caucasian peoples that would secure and protect their

own Caucasian-wide wealth, status, and interests none substantially rooted

within any proposed Armenian borders. Yet Tbilisi and Baku-based Armenian

elites, lacking sufficient social and demographic foundations in Georgia or

Azerbaijan failed to bring their ambitions to fruit. Their more powerful and

hostile Georgian and Azerbaijani competitors were not prepared to concede

positions to longstanding and hated Armenian capitalists and merchants who as a

result after 1918 were systematically driven down and out from both Georgia and

Azerbaijan. And when against their wishes the First Armenian Republic came into

existence Baku and Tbilisi-based Armenian elites instead of relocating self and

wealth to Armenia fled to safer havens in Europe or Russia.

When the First Armenian Republic came into being it was far

from a triumphant affirmation of vigorous or sturdy national development. It

was a travesty imposed on the Armenian people by Ottoman Turkey and lacked

durable core and solidity. It was imposed against the will of an unwilling

elite that regarded not Armenia but the wider Caucuses as its natural home. The

hollowness of the Republic was manifest in the 4 June 1918 Turkish-Armenian

Treaty of Batum. Armenia was reduced to a de facto dependent, apartheid

Bantustan-like entity. Some 800,000 people, many ill and starving remnants of

the Genocide, were squeezed into a 10,000 square kilometer patch of virtual

stone and desert around Yerevan, a vast refugee camp afflicted by hunger, disease and death. In this ‘independent Republic’ Turkey

obtained rights to use Armenian road and rail facilities to transport its

conquistador troops across the Caucasus. Under the pretext of maintaining law

and order it also secured rights to intervene in domestic Armenian affairs.

One significant clause in the Treaty highlighted the

intractable demographic complications within Armenian state borders. Intent on

organizing and deploying Turkish and Azerbaijani communities as a 5th

fifth column within Armenia in anticipation of a further offensive to terminate

the new republic, the Turkish state inserted a clause in the Treaty that

curtailed Armenian jurisdiction over these communities. The Armenian government

meanwhile was required to demobilize a substantial part of its army. Finally,

Turkish officers were to be stationed in Armenia to supervise implementation of

these clauses.

The conditions of the First Armenian Republic did not

essentially change with the formal conclusion of WWI, when the October 1918

Mudros Armistice expanded Armenian borders from 10,000 to 70,000 square

kilometers to include the Kars-Ardahan region.

Such were the inauspicious beginnings of the First Armenian

Republic. It was structurally unsustainable with no

historically matured social, class, economic, demographic or territorial

foundation. Like an unstable and withered tree in a fierce storm it lacked the

roots and foundations to resist as it was battered by economic, political, and

military crises and by Turkish aggression. Nothing that the forces then at the

head of the Republic did overcame any of these huge challenges. Armenia

remained a hollow state with its elites possessed of no popular social,

economic, and political vision or impulse to build genuine nationhood.

II. The hollow Republic

Through the three years of its life the leadership of the

First Republic failed to build broad, committed popular support for the new

state, support and commitment that could help compensate for the terrible

domestic and international weaknesses it suffered. In its domestic policies,

the ARF-dominated government appeared to represent and sustain only the elites,

the landlords, the Church, the capitalists, and factory owners as well as foreign

commercial interests. It did nothing radical or revolutionary to confront and

overcome any of the vital social and economic nation building tasks that would

have benefited the vast majority of the new state’s people – Armenian or

non-Armenian.

So, within a short span of time popular enthusiasm for the

Republic dissipated. The First Republic’s leadership failed to heed great

thinker Mikael Nalpantian. ‘Abstract nationalism,’ he wrote, is ‘senseless’. Naturally nation building requires national

language, art, culture, and literature. But it is never reducible to these.

‘Should we bother preserving our heritage, our language, our traditions, in a

word our nationality…?’ Nalpantian rhetorically asks. ‘Only if these give you

the right to enjoy the wealth of the land and thus free yourself from slavery

and poverty. During the first republic, with their most pressing social needs

disregarded, the mass of people grew indifferent to what became no more than

national and patriotic sloganeering serving interests other than those of the

common people.

Across three years the common people and the nation suffered

ceaseless unchecked socio-economic, political, military, ethnic-national,

refugee and national security crises. Slowly and surely the common people were

alienated from a government and state that failed to meet their immediate or

medium let alone long-term essential needs. The tiny elite meanwhile enjoyed

privilege and security, albeit fragile.

The republic’s structural crisis became acute in the last

year and a half of its life. The conditions of the people verged on the

catastrophic. ‘Extreme poverty and economic hardship prevailed across Armenia

(RP171)’ with the peasantry suffering particularly ‘terrifying poverty’. The

country was additionally ‘burdened’ by ‘unemployed and helpless refugees

(RP175).’ ‘Amongst the people discontent and impatience was evident (RP175).’

In his history of the First Republic Simon Vratzian its first Prime Minister

writes of a people menaced by ‘famine and economic crisis’, by the ‘breakdown

of food supplies’ and the ‘running down of stocks of flour (Note 4 - SV407-408,

411, 415).’

Amongst the common people disillusion and loss of faith in

the Republic grew rapidly, ‘giving idealist youngsters’ ‘ready ground’ to build

support for the Armenian Bolshevik opposition (RP171).’ For a population

‘suffering famine’ Bolshevik ‘slogans…that promised bread from Russia…and oil

from Red Azerbaijan’ ‘were attractive (RP188).’ ‘Armenian Bolsheviks’ Piroumian

adds ‘exploited every instance of protest and discontent across the entire

territory of Armenia (RP175-6).’ Simon Vratzian, also albeit contemptuously,

testifies to growing Bolshevik support as the Republic’s ‘hungry and

impoverished’ masses ‘became easy prey to Bolshevik propaganda’. For Vratzian

and Piroumian popular support for the Bolsheviks was only because the common

people are sheeplike ‘prey’ easily ‘exploited’ by Bolsheviks! That the ARF’s

failed to resolve even the most immediate problems confronting the people and

so enabled the relatively small Armenian Bolshevik organizations to secure

disproportionate influence does not occur to them!

The leaders of the First Republic also proved incapable of

building a cohesive popular national army. Garo Sassouni, a prominent ARF

leader, details this in his ‘The Armenian-Turkish War of 1920’. The Armenian

army reflected the new state and its leadership. It had no historical

traditions, no reserves, no hinterland to train and operate on. It was not a

national army but a broken-down remnant of the old Tsarist army, supplemented

by volunteer units from western Armenian provinces. Many of its leading officer

class had not lived in Armenia nor did they speak Armenian. Most were depoliticized with no nation building

ideals. The army was ill-trained and had no intelligence network worth speaking

of. Critically, wider socio-economic discontent with the government seeped into

the rank-and-file soldiers, themselves poor city dwellers and peasants.

Compounding the nation’s socio-economic troubles were the

‘endless wars (RP260)’ of which the ‘people were tired (RP260).’ From the

declaration of the First Republic to its end the Armenian government was in a

permanent military conflict over territories and borders with Georgia, with

Azerbaijan - over the contested regions of Gharabagh, Zangezur and Nakhichevan

- and with Turkey. More often than not Armenian military forces were defeated

or pressed back as their Georgian, Azerbaijani, and Turkish opponents generally

proved to be more effective, their positions enhanced by their leaderships’

nimble strategic international alliances. Parallel to endless territorial and

border wars the ARF government was also unable to resolve conflicts between

Armenian and non-Armenian inhabitants of the First Republic.

The debility of the First Republic was brought to the fore

during the May 1920 Armenian Bolshevik uprising. Despite having no deep roots

in Armenian society, Bolshevik cells and organizers enjoyed significant support

among wide sectors of the population. ‘In different regions of Armenia’ and

within ‘government structures and the military’ too the Bolsheviks ‘organized

uprisings’ that were ‘successful in Alexandropol, Kars, Nor Payazid

and Sarikhamish (RP188).’ Elsewhere, ‘in Ichevan’

‘locals joined the rebels’ and ‘captured the town (RP197).’ Simon Vratzian

writes that communists were ‘not a negligible force’ in Yerevan and enjoyed a

bigger following in Gyumri (SV402, 412-414).’ Conceding widespread support for

the Bolsheviks Vratzian with his usual tone of contempt for the common people

adds that a ‘weary population’ became ‘blind instruments of Bolshevik ambition

SV417)’.

In a puerile posture that brings no honor to the historian

or indeed the polemicist, both Rubina Piroumian and Lentrush Khurshutyan

present Armenian Bolsheviks as terrible ogres, as agents of a hostile foreign

state. Armenian Bolsheviks, according to them, lacked patriotism, were

anti-Armenian and opposed independent Armenian statehood. The Armenian

Bolsheviks, however, whatever their size, were in fact a legal political force

in Armenia who merely had radically different conceptions of Armenian

nationhood and statehood. In opposition to the ARF’s pro-Western orientation

they propounded a pro-Soviet one. Domestically, in opposition to the ARF’s

capitalist program they propounded a socialist one. This stance they argued was

the best option for the common people of Armenia. Simon Vratzian in his ‘The

Armenian Republic’ is thankfully free of narrow-minded prejudice. He describes

Armenian Bolshevik Alexander Miasnikyan as a ‘mature and serious Armenian’ who

worked together with other ‘enlightened and unquestionably patriotic Armenian

Bolsheviks (SV601, 603).’

To suppress the Bolshevik revolt the ARF government could

not rely on the Armenian army. Composed primarily of eastern Armenian soldiers,

army ranks reflected the discontent and grievance that was generating

pro-Bolshevik sentiment among the common people. So, for ‘repressive power’

they deployed ‘old western Armenian fedayeen and other fighting units’ also

‘composed of western Armenians (RP195)’. The ‘extreme’ violence (RP196)’ they

meted out to the ‘masses in revolt (RP196)’ is justified by Piroumian on the

grounds that the common people were ‘Russophiles’ ‘indifferent’ to ‘idea of the

nation’s independence (RP196)’, an independence that it was ‘necessary to

protect’ ‘whatever the costs (RP196).’ Did Piroumian not ask herself what the

Republic’s ‘independence’ could possibly mean to a people suffering endless

poverty, hunger, and war!

The aftermath of the May 1920 Bolshevik uprising exposed the

ramshackle character of the First Republic. Correct, ‘the disturbances were

suppressed, but the disillusion and loss of hope that followed, among the

people and even in government and leadership circles was deep and enduring

(RP199).’ Even in the ‘army as a result of Bolshevik propaganda there was a

breakdown of discipline (RP200).’ To survive the government would have to ‘push

back all the forces seeking to bring it down’, ‘restore law and order and peace

in the country’ and ‘rebuild the damaged administrative, transport, supply and

legal and judicial systems (RP283).’ Here was a description of a state on the

edge of breakdown, even disintegration.

To compensate for Armenia’s territorially, economically, and

militarily weak position vis-á-vis its neighbors and the regionally active

great powers, the sole foundation for sturdy statehood was a common people

fired by hope, enthusiasm, and optimism for their daily existence and their

future that would seep into the state apparatus, the ranks of the army and all

areas of state life. But the ARF constrained by its desire to cater to the

needs and interests of Western powers and to those of the Armenian elites, the

Church, the landlords and the wealthy, failed to build such a foundation, a

foundation that would centralize the nation’s land and wealth and put it at the

disposal of the common people who constituted the essence of the nation. This

was beyond the ARF and its allies.

Thus in September 1920 the Armenian

state was in no position to resist the onslaught of Kemal Ataturk’s Turkey, an

onslaught during which it intended to retake the Kars-Ardahan region as a

minimum and possibly wipe Armenia off the political map altogether.

Footnotes

Note 1

Rubina Piroumian, ‘Armenia During the Web of ARF-Bolshevik

Relations -1917-1921’, 421pp, 1997, Yerevan. Page references as RP followed by

page number as in RB421.

Piroumian’s is a mean-spirited, anti-human and

anti-democratic nationalism that is shamefully evident in a passage where she

takes Stepan Shahumyan to task for his concern not only for Armenian deaths

during the genocide years but for the First World War deaths of thousands of

innocent Turkish and Kurdish common people too (RP45).

Note 2

Lentrush Khurshutyan, ‘The 1920 Division of Armenia’ 316pp,

2002, Yerevan. Page references as LK followed by page number as in LK316

Note 3

For the moment we leave aside consideration of the

anti-democratic character of projects to build exclusive ethnic-national states

in regions that had for centuries been hugely diverse, nationally,

demographically, culturally, and otherwise. For example, in Zangezur/Syunik,

Gharabagh/Artsakh and Nakhichevan the demographic composition of each area was

a patchwork of different peoples. They were inevitably fought over in the

process of nation-building, with ethnic cleansing an almost certain step to be

taken by whatever victorious party in the battle to incorporate these into its

ethnic-nation state. Such complications would make ethnic-nation state

solutions a disaster for all common people of the region.

Note 4

Simon Vratzian, ‘The Republic of Armenia’, 704pp, 1993

Yerevan. Page references as SV followed by page number as in SV704.

|

|

Eddie

Arnavoudian holds degrees in history and

politics from Manchester, England, and is ANN/Groong's

commentator-in-residence on Armenian literature. His works on literary and

political issues have also appeared in Harach in Paris, Nairi in Beirut, and

Open Letter in Los Angeles. |