Armenian News Network / Groong

The Uprising

of the Armenian lords of Garabagh-Gaban

Armenian News Network / Groong

December 31, 2022

By Eddie

Arnavoudian

LONDON, UK

The 18th century uprising of the Armenian lords

of Garabagh-Gaban

Something

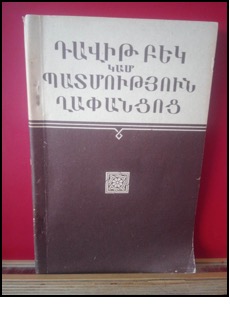

of a primary source, ‘David Beg or the

History of Gaban’ by 18th century Mekhitarist priest Ghugas Sepasdatzi (112pp, 1992, Yerevan), is a thought-provoking

account of the 1721-1730 uprisings of Armenian feudal estates in the Gaban-Garabagh region against both Persian state forces and

their local Turkish allies and against the Ottoman State that was then intent on

seizing the Caucuses from a faltering Persian power.

This

slim volume, by virtue of its Armenian authorship, offers material for

scrubbing away the romantic mythology that has developed around the battles led

by David Beg, commander of the Armenian rebels, at their strongest point.

Without exception the Garabagh Uprisings, in

historiography and in fictional literature, have been depicted as a national

movement representing the whole of the Armenian people. Ghugas

Sepasdatzi shows it otherwise.

This

slim volume, by virtue of its Armenian authorship, offers material for

scrubbing away the romantic mythology that has developed around the battles led

by David Beg, commander of the Armenian rebels, at their strongest point.

Without exception the Garabagh Uprisings, in

historiography and in fictional literature, have been depicted as a national

movement representing the whole of the Armenian people. Ghugas

Sepasdatzi shows it otherwise.

In

a more focused account Sepasdatzi records a reality

in which at every step it was Armenian feudal lords and leaders and not the

people who determined Armenian ambitions and strategy. This was not an age in

which the ‘democratic will’ of the people was operative, in Armenia or

elsewhere! Rather Sepasdatzi’s narrative tells of an

uprising of the Armenian feudal nobility who, dedicated to their own autonomy

and freedom from Persian and Ottoman power remained nevertheless at the same

time dedicated to the continued feudal subjugation and oppression of the

Armenian peasant, then the majority of the Armenian people.

In

1721 Armenian feudal principalities sensing an opportunity to extricate

themselves from the claws of a vulnerable Persian Empire that privileged local

Turkish estates, turned to their neighboring Georgian monarchy for help. To

lead them in their endeavors they succeeded in recruiting David Beg from the

Georgian Armenian nobility. Under his remarkable military-organizational

leadership the Armenian rebels fought with success so great that they were able

to put in play a larger strategic ambition – having weakened Persian and

Ottoman power they aspired now to a degree of autonomy under Georgian auspices.

It

of course speaks to an organic weakness of the Armenian Garabagh

principalities and of nation formation at the time that they could not throw up

a local leader for their ambition. In the entire effort of war and political

maneuver David Beg remained critical to Armenian success. Without him there

were no local forces capable of compelling Armenian elites to united strategic

action. Indeed, as is evident in this volume an already fragile, precarious and unstable Armenian unity under David Beg

disintegrated rapidly following his untimely death in 1728. Mkhitar Sparabed who succeeded David Beg was ‘murdered by his own’.

But even before David Beg’s death Armenian estates

under his leadership were engaged in mutual intrigue, deception, plot and treachery that foretold great ills and had on

occasion to be controlled by executions.

Ghugas

Sebasdatzi’s horrifying accounts of military

engagements that were simultaneously endless episodes of mutual slaughter,

pillage, plunder, arson and ethnic cleansing on all

sides tempers any unqualified nationalist, democratic or progressive labels

that are readily attached to the 1721-1728 uprising. A few examples from the

Armenian side are instructive. At one point, Sebasdazi

writes that ‘having set camp in a fort called Shnher’

David Beg ‘invited the leader of Datev and explained

his ambitions in the land. He said “We intend to

totally clear this land of all foreigners”. He then gathered together the men

of Shnher and went on to strike and plunder Turkish

villages and seized all their belongings (p21).’

Further

on, we read of an Armenian military leader Toros ‘pursuing Sabi

Ghuli’, ‘slaughtering eighty of his men’ and going on

‘to destroy three Turkish villages, seizing all their property and returning to

Manlev (p31).’ ‘David’s forces traveled through all

of Gaban inspecting and searching and wherever they

found Turks they cut them down with their swords until

they totally eliminated them from Gaban (p33).’ There

are plenty of similar examples, and of course examples of Turkish forces doing

the same to Armenians and indeed of Armenian forces plundering Armenian

villages (p33)!’ This tragic and

sobering story of mutual barbarity was alas to be repeated in different forms

across the centuries.

Of

course, the slaughter of opponents and the cleansing of their populations from

their local villages was, in a sense ‘par for the course’ for all

socio-political-military forces at this stage, irrespective of nationality. But

this does not excuse a post-facto sanitizing of these aspects of the uprising

and its presentation or reconstruction in patriotic shades that conceal not

just the savage violence but the absence of a genuine democratic nationalist,

nation-building drive.

Nevertheless,

from the standpoint of the remnants of an ancient Armenian feudal nobility

David Beg’s accomplishment during his short ‘reign’

was in many respects quite remarkable. To set about seizing the Caucuses from

Persia, the Ottoman Empire had first and foremost to deal with and overcome

David Beg. And subduing him proved no easy task. The Ottomans suffered repeated

heavy blows from their Armenian adversaries and were saved from further

humiliation by ‘divine intervention’ in the form of David Beg’s

death by fatal illness.

David

Beg evidently was a man with his own independent ambitions and with an acute

eye of where Armenian strategic interests lay. Though assigned his role by the

Georgian monarch who hoped to use him to extend his authority over a wider

swathe of the Caucuses, David Beg was no subservient tool. Despite early visions

of autonomy within Georgian auspices, when he emerged dominant Beg entered into

a pact not with Georgian but with Persian power as the latter had begun to

slowly recover.

Ghughas Sebasdatzi does not explain this apparent

shift. But he offers material that goes some way to understanding it. Though

David Beg emerged in prime position, the historically pro-Persian Turkic

principalities in the region had not been eliminated. Negotiating their

acquiescence to his supremacy would be easier with his domain as a Persian

rather than a Georgian protectorate. Moreover, in any contest between Georgian

and Persian power the latter was more likely to prevail. So, David Beg, acute

as he was, tilted towards Persia.

Definite

class interests drove Garabagh’s Armenian elites to

revolt against Persian rule. Their very existence was in danger from an

alliance of the Persian throne with local Turkish lords who were the favored

agents of Persian control. Armenian estates with their long association with

Georgia and Russia could not be reliable agents of the Persian state. The

rebellion by Armenian lords and the enhancement of their military, political

and social status was part of their struggle for survival against foreign

control and oppression.

But,

what about the role and interests of the Armenian peasantry, the majority of

the Armenian people some may ask? Though fiercely exploited by Armenian elites,

the Armenian peasantry were nevertheless also fatally menaced with

expropriation and destruction in the Persian and Turkish sweep against Armenian

feudal estates. To preserve their families, their homes, their land and their villages they too would be more secure in

independent statehood or even in an autonomous protectorate. Such factors

together with traditional feudal servitude would explain the readiness and

enthusiasm of Armenian peasants who fought Turkish, Persian and Ottoman lords

and soldiers.

During

the Garabagh Uprisings there appear to have been

grounds for a ‘united front’ of Armenian classes, a common interest that would

momentarily set aside the inherent contradiction between the Armenian feudal

lord and the Armenian peasant. It was a common front that reminds one of the

same in the great 5th century Vardanants

war against Persian power. But alas due to the overriding socio-historical

factors of the times the 18th century ‘common front’ proved of

little historical value to the common people who through subsequent centuries

were to be and continue to be violently driven from their lands.

Ghugas

Sepasdatzi’s is a proud account of the 1721-1730

events for albeit a clash of minor feudal estates, for a short period, against

the grain and against a history of centuries of oppression, Armenian elites

emerged dominant. But alas only for the shortest period. The Uprising ended in

failure and in its wake these remnants of semi-autonomous Armenian estates

slowly withered and then were extinguished after the Russian conquest of the

Caucuses.

There

is however little doubt that right into modern times the resilience and the

spirit of resistance demonstrated by the Armenian people of Garabagh,

always in desperate struggle for the right to live in their homelands has

always been reinforced by the memory of the 18th century Uprisings

of the Armenian Lords of Garabagh.

|

|

Eddie

Arnavoudian holds degrees in history and

politics from Manchester, England, and is ANN/Groong's

commentator-in-residence on Armenian literature. His works on literary and

political issues have also appeared in Harach in

Paris, Nairi in Beirut and

Open Letter in Los Angeles. |