Armenian News Network / Groong

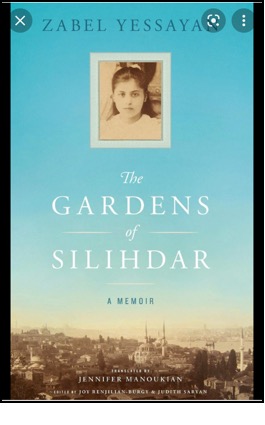

‘The Gardens of Silihdar’

an autobiography by Zabel Yessaian

Armenian News Network / Groong

June 29, 2022

By Eddie Arnavoudian

LONDON, UK

‘The Gardens

of Silihdar’ by Zabel Yessaian

‘The Gardens

of Silihdar’ by Zabel Yessaian

Zabel

Yessaian (1878-1943) was one of the outstanding

Armenian writers of the late 19th and early 20th

centuries. Possessed of literary ambitions, when but 12 years old, confident and audacious without prior arrangement she

knocked at the door of well-established woman novelist Srbouhi

Dussap. During what was to be a warm encounter Dussap warned that ‘the male writer can succeed even when

mediocre, the woman cannot.’ Yessaian was not

discouraged. She had both talent and a stubborn will and against all odds she

secured a prominent place in the annals of Armenian literature.

Amidst

Yessaian’s substantial output is the autobiographical

‘The Gardens of Silihdar’. Recalling her first 12

years it was the first part of an intended series that was never to be completed.

Yessayan fell victim to the Stalinist purges of the

1930s. Nevertheless, though slim, ‘The

Gardens of Silihdar’ is remarkable on many levels. In

versatile, often poetic prose the narrative unfolds to skilfully

render graspable those almost intangible processes of individual emotional, psychological and intellectual formation and development.

Against a background of oppression and restraint Yessaian

and her generation experienced, her reminiscences tell of those intricate

stages of a child blooming into a free-spirited, daring, adventurous young

woman preparing to resist and fight to live an emancipated life.

The

social and national context of Zabel Yessaian’s early

years was Istanbul’s substantial Armenian community where she was born. Here

‘The Gardens of Silihdar’ becomes simultaneously a

critical reconstruction of Armenian-Istanbul prior to the 1915 genocide.

Damning descriptions lay bare ugly truths of the community’s iniquitous class

structure, of its arrogant and haughty elites, of its oppressive social and

domestic life, and centrally of the subjugated position of women.

One

recoils when reading of the Church establishment’s savagery as it buried

recalcitrant individuals in dark underground dungeons. In a remarkable moment

describing the appalling reality of schools in a community riven and corrupted

by class inequality and humiliating poverty, Yessaian

writes that ‘at the age of 12 I already knew the external world from within the

world of school’. The accounts that follow are horrific and shocking. One recognises here the same world of Yeroukhan's

short stories, and those too of Dikran Gamsaragan, Levon Pashalian and others that together are indictments of the

rotten core of Istanbul’s Armenian community in which the immense majority

suffered at the hands both of the Ottoman state and the Armenian elites.

But the reader is also exhilarated by tales of

Zabel’s father and of her uncles and aunts who in one way or another defied and

resisted both Ottoman oppression and social and class injustice. The young and

impressionable Zabel is told stories of men rebelling against injustice and

fleeing to the mountains to become freedom fighters. She absorbed accounts of

plebeian smugglers opposing the Ottoman state’s granting of tobacco monopolies

to French firms, a measure that destroyed the livelihood of local producers

(p204-205). Images of contempt for the exploited poor run together with

inspiring recollections of Zabel and her aunt receiving collective solidarity

and generosity from the ‘lower’ classes, solidarity and generosity never

extended by the better off (p257). All this no doubt fell on the fertile soil

of Zabel Yessaian’s rebellious and generous

personality.

But the reader is also exhilarated by tales of

Zabel’s father and of her uncles and aunts who in one way or another defied and

resisted both Ottoman oppression and social and class injustice. The young and

impressionable Zabel is told stories of men rebelling against injustice and

fleeing to the mountains to become freedom fighters. She absorbed accounts of

plebeian smugglers opposing the Ottoman state’s granting of tobacco monopolies

to French firms, a measure that destroyed the livelihood of local producers

(p204-205). Images of contempt for the exploited poor run together with

inspiring recollections of Zabel and her aunt receiving collective solidarity

and generosity from the ‘lower’ classes, solidarity and generosity never

extended by the better off (p257). All this no doubt fell on the fertile soil

of Zabel Yessaian’s rebellious and generous

personality.

Yessaian’s recollections of the plight and subjugation of women in her family and

her neighborhood community are particularly commanding. Her mother was forced

to marry at 14, in part to escape the attention of the savage Ottoman yenicheri soldiers. Yessaian

still remembered times when Armenian women were almost prisoners in their home

and not even allowed to go to Church. Against the restrictions she suffered and

moved by her own radical dispositions, like many young women in similar

circumstances Yessaian dreamt of ‘being a boy, a

bandit, taking refuge in the mountains…fighting for justice (p235).

Here

and throughout, she shows herself uncompromising in demands for women’s rights

and in hatred for poverty, class exploitation and national oppression. And as

she recounts incidents, feelings,  and reactions she offers a universal radical and

democratic feminism, one that fixes the aspiration for women's emancipation as

part of the collective ambition of all oppressed nations and classes for

emancipation from all injustice.

and reactions she offers a universal radical and

democratic feminism, one that fixes the aspiration for women's emancipation as

part of the collective ambition of all oppressed nations and classes for

emancipation from all injustice.

Growing

up at the fluid intersection of different social classes Zabel Yessaian imbibed a remarkable range of early childhood

impressions. Her family and upbringing brought together men and women from

across the Armenian community’s class spectrum. The detail of these

recollections reveals something of the symbiotic, dialectical relationship

between the formation of individual personality and the 'spirit of the times',

between the outlooks and ideas, the visions and hopes of an age and the stamp

of individual personality, character, and ambition.

In

beautiful clear prose rich with defining detail, one sees how the ‘spirit of

the age’ is passed on and develops through a complex web of personal relations

across families, extended families, and local communities, as well as relations

between Armenian and Turkish communities. It is indeed part of the power of

this volume that progressive or reactionary outlooks and attitudes, indeed the

entirety of the socio-political realities of the day that it so brilliantly

reproduces, emerge sharply as moments of intimate and emotional personal,

individual experience.

Our

times a century on are lit by little hope. But as

Naguib Mahfouz reminds us ‘to despair is to insult the future’, that is to

insult our children and our grandchildren. Yessaian’s

literary legacy can help combat despair, can help us stand firm and have faith

in a future that has been so rampantly endangered by the elites of today who

are the offspring and of a type with the elites criticized in ‘The Gardens of Silihdar’.

|

|

Eddie Arnavoudian

holds degrees in history and politics from Manchester, England, and is ANN/Groong's commentator-in-residence on Armenian literature.

His works on literary and political issues have also appeared in Harach in Paris, Nairi in Beirut and Open Letter in Los Angeles. |