Armenian News Network / Groong

Stepan Zorian: An Outstanding Soviet Era Novelist’s Posthumous

Works

Armenian News Network / Groong

November 28, 2021

By Eddie Arnavoudian

LONDON, UK

Unflinching

critical engagement in Soviet Armenia

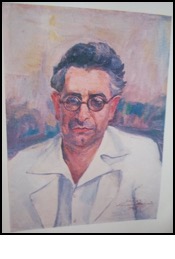

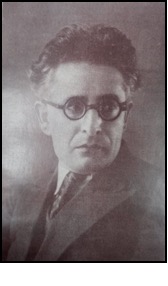

Short story writer and novelist Stepan Zorian

(1889-1967) described himself as a ‘chronicler of his times’. His three volumes

of posthumously published notes, letters, articles, fragments from unfinished

short stories and novels and especially his diaries make for riveting reading

about life in Soviet Armenia. They are full of frank and revealing insight as

they expertly chronicle the Stalin era, the hardships of everyday life in

Armenia, the traumas of Armenian history, the fragility of the Soviet Armenian

state, the reality of Great Russian and other national chauvinisms, the Cold

War, the threat of global nuclear catastrophe, opinions on writers and poets as

well as on his own literary career and much more.

Like the first and second volumes, this third one (336pp,

2013, Yerevan) has the quality of primary source material and the quality of

fine art too as the author with vivid sketches of individual experience, emotion and sensibility, his own included, captures a sense

of those invisible but overarching social relations and forces that shape

lives.

Illuminating comments on painting, sculpture, architecture and literature show him unafraid to challenge

Soviet orthodoxy or the more bombastic Armenian patriotic traditions. The

almost deified Soviet writer Maxim Gorky is dismissed. ‘I was never attracted

by any of his works’. His ‘characters are artificial’ and his most famous novel

‘Mother’ ‘is boring, verbose, artless and unconvincing.’ Zorian’s

judgment of poet Siamanto, victim of the genocide, is

no less withering: ‘wooden language and words plucked from dictionaries’;

instead of ‘honest emotion’ ‘bombastic sentences’, ‘accumulations of

words…bombastic words.’

Despite the great honour he

enjoyed in the Soviet era Zorian had no time for the

bureaucratic USSR party apparatus whose officials tiresomely and repeatedly

heralded a degenerate Soviet Union as a triumph of socialism. Despondent, in a

December 1966 diary entry he warmly recalls the pre-Stalinist ‘1920s… (as)

different days. Then there was enthusiasm, faith and a

positive outlook. These have now all been forgotten. Petty egoism prevails  everywhere… What is going to be the

end of this…’ Zorian died in 1967, just over two

decades before ‘the

end’ in the form of the USSR’s collapse.

everywhere… What is going to be the

end of this…’ Zorian died in 1967, just over two

decades before ‘the

end’ in the form of the USSR’s collapse.

Ruminations on tiny landlocked Armenia grasp its existential

vulnerability even during the Soviet age. ‘The phenomenon of mass emigration’

that had blighted the larger homelands during the 19th century

‘continue to this day’. Like yesterday, in Soviet Armenia too ‘rivers have

flowed beyond its borders to irrigate the fields of other nations, its human

resources migrated to build other nations’ cities, its intellectuals built

other nations’ science.’ With Armenia weakened and now ‘bereft of its

(historical) lands’ ‘the outlook for its continued survival is bleak.’ Our

nation ‘is like an irreparably broken plate, its fragments strewn far and

wide’.

Passing entries capture wider truths. The times are menaced

by unresolved national animosities. The ‘brotherhood (of peoples) is an

illusion.’ National antagonisms during the Soviet age have been suppressed but

not eliminated. ‘Rather than the sermon of brotherhood it is the law that

restrains.’ Meanwhile Great Russian chauvinism corrupts the Armenian language.

‘We have to have permission’ ‘to use our own native words’. ‘The defense of

(Armenian) terminology is damned as nationalism!’ ‘What usurpation!’

Zorian’s register of his own personal drama

is as profound as it is moving. 70th birthday greetings ‘leave a bad

taste’. They remind him ‘of the years during which my bright dreams and so many

creative ambitions died.’ He remembers the Stalinist purges when ‘countless

men…innocent comrades and friends…were exterminated.’ Five years on as the

December ‘snow settles on roofs and trees…I feel childhood returning and

despite being 75 I want to run and play!’ But still there is no escaping

memory. Recollection of ‘comrades lost and banished’ cause deep pain. Revealing

enduring wisdom, Zorian  continues:

continues:

‘Albeit 75 I do not feel old. I

remain captivated by the beauties of nature and of life, exactly as I was when

young. Moreover, my mind is as active as ever, as is my desire to work. Perhaps

this itself is a sign of age…we want to leave a legacy behind. On the other

hand, the desire to work is perhaps an instinct that seeks to dim the thought

of death. Yet I now think of death more frequently …It does not matter how much

one grasps it as an inexorable law of nature, death remains the greatest

tragedy of a human life.’

The available portions of Zorian’s

diaries are invaluable. Alas, only tiny segments survive. For personal and

family safety at the height of Stalin’s purges, he and his family burnt the

bulk of diaries Zorian had started keeping in 1910. A

huge masterpiece of art has been lost beyond any recovery. But that which

remains together with all Zorian’s posthumous

writings are absolutely indispensable to any historian of Soviet Armenia and of

Soviet Armenian art, culture and literature.

|

|

Eddie Arnavoudian

holds degrees in history and politics from Manchester, England, and is ANN/Groong's commentator-in-residence on Armenian literature.

His works on literary and political issues have also appeared in Harach in Paris, Nairi in Beirut and Open Letter in Los Angeles. |