Armenian News Network /

Groong

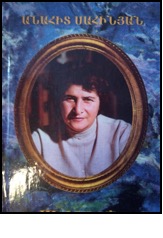

Anahit Sahinyan reveals the origins and nature of the Armenian

Republic’s ruling elites

Armenian News Network / Groong

November 15, 2021

By Eddie Arnavoudian

LONDON, UK

Prominent Soviet era

novelist Anahit Sahinyan’s (1917-2010) ‘Blowing in

the Wind – Volume 2’ (2005, 460pp, Yerevan) throws a sharp and critical light

on the origins and nature of the elites that are currently leading and

destroying the Armenian nation and state. Herein is the enduring value of a

book published 16 years ago! The volume is a collection of socio-political

commentaries penned during the decade after the collapse of the USSR and the

1991 formation of the Third Armenian Republic. In all her commentaries Sahinyan is an uncompromising advocate for the common

people against the brigandage of corrupt Soviet era elites and against the

equally pernicious new ruling classes of the Third Armenian Republic.

Taken together through

these articles the reader is pushed to an inescapable conclusion. The birth of

the 1991 Third Republic was no crowning achievement of a popular democratic

revolution. It was the triumph of a new usurping elite determined to ensure

that it was now ‘its turn to gorge on corruption’. The so-called democratic

revolution was in essence an expropriation of the entirety of the national

wealth created by the Armenian people by a small proto-capitalist class born

from the bowels of the disintegrating Soviet state bureaucracy. Party

apparatchiks, segments of the intelligentsia and careerists all devoid even of

a whiff of democratic morality and principle leapt onto the capitalist ship

from a sinking Soviet one, there to make new fortunes. The masses, the people,

were victims not beneficiaries of the Third Republic.

Exposing the old Soviet

elites’ obnoxious parasitism, Sahinyan shows the new

rising from the marsh as scum to the surface, seizing leadership of the mass

movement, robbing aid intended for the impoverished, for the victims of the

earthquake and for.

Armenian refugees fleeing

Baku. These new elites began making their fortunes by theft, by stealing the

people’s wealth created across the 70 years of Soviet rule (p330). Benefiting

only the new elites, a so-called “democratic revolution” reduced the majority

to penury and impoverishment.

The Armenian Church and its

privileged clergy come in for especially sharp judgment. Enough of denouncing

Soviet Church repression Sahinyan exclaims. The

Armenian Church has now had 12 years of freedom. But what has it given except a

multiplication of Churches and a rise in the numbers of clearly well-off

priests (p339-340)!

Albeit scathing of Soviet

era degeneration, by the turn of the 20th century witnessing

continuing ceaseless dispossession of the people Sahinyan’s

evaluation of the old order becomes more explicitly positive. Despite Stalin’s

terrors, despite the tyranny of the state bureaucracy, Armenia in the Soviet

era registered remarkable economic growth and a flourish of science, art, culture and literature (p294) that was available to all. Today,

with the fruits of its labour stolen by a new ruling

class, the people suffer not only material want but spiritual famine too

(p292-294).

Despite Pashinyan’s

so-called “velvet revolution”, corrupt and selfish elites still rule the roost

in Armenia. They are in sum the inheritors of the early post-Soviet elites that

Sahinyan so passionately opposed. They are in essence

no different from the old elites in their complete disregard for the needs of

the common people upon whom they leech.

Readers of all persuasions

will find something to quibble with in a volume marked by often confused or

contradictory arguments. But one thing is incontestable, in every one of her

judgments in contrast to elites of all colours Sahinyan remained unwavering in commitment to the

well-being of the common people.

If one is to talk of

genuine, authentic patriotism then Sahinyan was one

such patriot from whom we can learn today. Let us recall Mikael Nalpantian! No amount of nationalist rhetoric, no amount of

glorification of national culture and history will ever approach genuine

patriotism if it does not put the needs and interests of the common people at

the unconditional forefront of its concern. Sahinyan

did so, the Pashinyan revolution did not and does not!

Ending, let us recall

Anahit Sahinyan the novelist. With their critical

realist embrace of Soviet Armenian life from the 1920s to the early 1960s her

trilogy (‘Crossroads’ 1946, ‘Thirst’ 1955 and ‘Longing’ 1974) are enduring

artistic achievements, authentic registers of individual, social, political and

economic relations of the times. These together with her voluminous non-fiction

writing is a legacy to be treasured.

|

|

Eddie Arnavoudian

holds degrees in history and politics from Manchester, England, and is ANN/Groong's commentator-in-residence on Armenian literature.

His works on literary and political issues have also appeared in Harach in Paris, Nairi in Beirut and Open Letter in Los Angeles. |